Back in c. 200 BC, Antiochus III "the Great" of the Seleucid Empire annexed the former Ptolemaic holdings in the southern Levant, including Judea. The Judeans were at first rather welcoming to the change of affairs. They had been living for centuries under multinational empires, rather peacefully as well. Antiochus was a warrior king on the rise, wealthy and fresh from many a conquest and reconquista. He was able and willing to offer increased autonomy and reduced taxation compared to what they had under Ptolemaic rule. This was not to last long.

Ten years later Antiochus III was defeated in a war by the Romans and their Greek allies. Harsh conditions were imposed, including massive war reparations. The following Seleucid kings struggled to keep their empire in good order. Meanwhile, during over a century of Greco-Macedonian rule, many Judeans had been hellenizing. Traditionalist and Hellenophile factions started to compete for influence in local politics and eventually for the High Priesthood in Jerusalem. The Ptolemaic and Seleucid courts didn’t go heavy handed into this process during it's early stages, but certainly sought ways to have their local influence grow.

A short lived revival of Seleucid power happened under Antiochus IV "Epiphanes" (175-164 BC). By now, Perseus of Macedon was trying to challenge Roman dominance in Greece, and Antiochus was a potential ally. The regents of young Ptolemy VI launched a failed invasion of Syria, quite likely at Roman instigation. In retaliation, Antiochus almost managed to fully conquer Ptolemaic Egypt, though threats of a new war with Rome made him withdraw. Right before his Egyptian campaigns, he meddled with local politics in Judea, deposing High Priest Jason to install his rival Menelaus. While Antiochus IV was in Egypt, Jason and his followers captured Jerusalem and besieged Menelaus in the citadel. Antiochus, returning from Egypt, unleashed the Seleucid army to sack the city and its temple. His reign marks the beginning of increased hostility among Judean factions and direct imperial intervention, leading to the Maccabean Revolt against Seleucid rule.

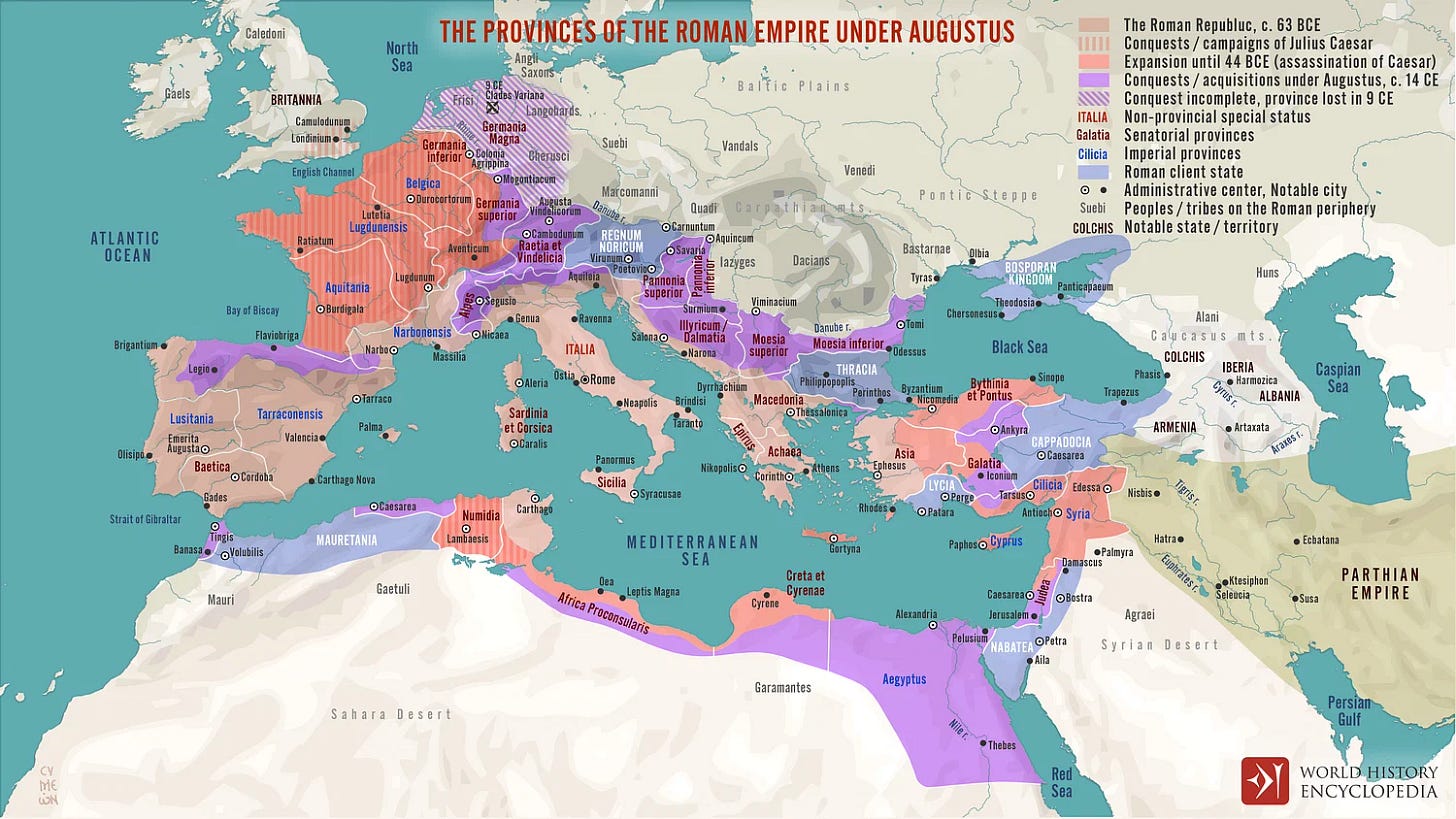

The following period is one of great militancy, centralization and religious reforms in Judea, and of frequent dynastic wars in Seleucid Syria. Hostilities last for the next 30 years, until Judean leader John Hyrcanus submits on friendly terms to Antiochus VII "Sidetes" (yes, half of the Seleucids were named Antiochus and most of the rest Seleucus, while all male Ptolemies were named Ptolemy and most loved their sisters). John Hyrcanus will soon join Antiochus VII in the last major military campaign in Seleucid history, trying to reconquer the eastern Satrapies. After Antiochus dies to a Parthian ambush in 129 BC, the Seleucids find themselves in constant dynastic wars for 7 decades, until the annexation of Syria by the expanding Roman Republic. By 110 BC Judea is a fully independent kingdom, lasting until 63 BC and its submission to Rome. In 37 or 36 BC, Herod I "the Great" seizes the throne and further incorporates the Judean state into the Roman one.

Roman rule is to become even more polarizing than the late Seleucid one. As the Roman Republic transforms into the Empire, the Romans gradually bring with them construction projects, harsh taxes, cultural and religious interference on an unprecedented scale. Large parts of the already militarized Judean society are split into factions with religious and class undertones. Their zeal, infighting and failure to cooperate effectively would be eventually used in Monty Python's “Life of Brian” to satirize 20th Century left-wing politics.

The Greco-Roman religion was a form of polytheistic paganism, traditionally tolerant to foreign deities. It was starting to drastically change though, while the two cultures were at severe odds at that point. Judeans had served as mercenaries in Ptolemaic and Seleucid armies for 3 centuries.1 Seleucid direct interference and subsequent Judean independence, coupled with increased monotheistic zeal and militarization, forged a society that wouldn't easily accept direct foreign domination. In contrast, Roman statesmen were by now generally expecting conquered populations to submit without too much trouble. Roman diplomacy caused divisions, the military juggernaut marched in and cultural trappings followed right behind. Furthermore, the Roman state now spanned the entire Mediterranean and beyond. The upstart system of Imperial rule was looking for more centralizing ideas and sacred symbols to impose on it's massive and diverse populace.

An early form of such practices was the concept of the God-King. Alexander III "the Great" was the first to force this concept into the Greco-Roman world. Many Hellenistic kings, including Seleucid ones, and nonetheless the pharaonic Ptolemies, soon followed his example. Still, the practice wasn't widely normalized outside of Egypt and was generally not enforced. When Roman Emperors started to pose as gods, the concept would have been especially foreign to the idol-averse and monotheistic Judeans. Imagine being forced to worship a statue of Caligula - or, better - try replacing Caligula with any current politician or billionaire. Should feel somewhat closer to how many of them must have felt.

A series of revolts, spanning 130 years (6-136 AD) followed the Roman annexation of Judea. During those times, militant messianic cults promised the defeat of the Roman oppressor and the establishment of the proper Judean state or era. Most of them ended with increasingly harsh suppression and loss of civic and religious rights for the locals. Many Judeans fled, leading to a diaspora all over the classical world. So far, a number of them, mostly mercenaries, had settled in foreign cities under their Hellenistic employers. During the Jewish–Roman wars, a significant portion of the population fled the region. Many of these migrants and refugees rose in revolt at their new home cities in 115 AD. These series of particularly brutal wars, often ignored or taken out of context, lead to the deaths of hundreds of thousands on both sides and left a mark that still echoes through history.

As the Roman Empire (im)matured, attempts at establishing a universal imperial religion and the related religious conflict intensified. Emperors would try to impose their favored state cult and deities would decline with their champion’s death. The prized status as suppreme method of control was eventually won by Christianity.

I shall from now on indulge in wrong-think and speculation. Proceed at your own risk.

Since a very young age, I was wondering how Christianity - the peaceful religion of the poor, the outcasts and the slaves - could come to dominate the Roman world. Later, I learned of its persecution of pagans and heretics, which made much more sense for a highly centralized cult. It also made sense with what was to follow in history; world religions (literally or not) sponsoring holy wars. I'm not claiming the average Christian is to blame. I just was - and remain - very curious about the whole picture. Over the years, what made the most sense to me is that Christianity was forced to it's rise by elements within the Roman ruling classes, who thought it best suited their interests; their rise to power or domination of their subjects. Some powerful statesmen saw significant benefits, and not because they were nice folk or redemption dealers making amends for Christian trauma. That’s not how empires or centralized states function.

The Flavian family (and dynasty) and their circle are a very curious case. They are pretty much associated with Christianity from its very start, even providing popes, martyrs and saints. These two documentaries argue quite convincingly - though not always with conclusive evidence - that the Christian Cult was originally a Flavian construct, during the times of Vespasian and Titus. Father and son, they personally commanded the Roman forces against one of the largest Judean revolts (66–74 CE). Their interest in controlling historical, cultural and religious narratives in Judea and the empire is quite well documented. Later, Constantine I "the Great" of the Neo-Flavian, or Constantinian dynasty, was the emperor who did the most to establish Christian dominance. The story of him becoming a Christian in his deathbed sounds like a very convenient tale, like the one with the flying warlike cross before one of his victories. History is - quite boringly - mostly written by the victors, while persecution and fire erase much of what could provide counter-narratives.

One thing I'm fairly sure of is that many of the Christians supposedly thrown to the lions or persecuted in other ways, where actually Judean rebels. Much of the “Christians-to-lions” period falls within the timeframe of the Jewish–Roman wars and their aftermath. The Judean rebels were the militant threat to the establishment. The ones who invited further vengeance by killing many thousands of Greek and Roman civilians. Maybe some peace loving Christians got caught in the crossfire, due to similar ethnic and religious characteristics. Maybe some were followers of various unwanted or heretical sects that didn’t serve or directly opposed contemporary imperial power. Maybe the truth is actually even further from what we were told. In the end, Church and State certainly did - and still do - some good old recuperation of history. Always assisted by The Science that persecutes real science.

Likely contributing to militarization through experience.