The Sparta You've Never Heard About - Part III

Sparta and the early stages of the Ancient World War.

…Continued from Part II

This part might be especially messy if you haven’t read the previous ones and aren’t familiar with the era. Without enough Sparta-specific information to turn into a coherent storyline, from now on we’ll follow events directly and indirectly related to Sparta at the same time.

Lycurgus of Sparta and the Ancient World War (c. 222-210 BC)

The death of Cleomenes in 219 BC found Sparta with two new kings. Agesipolis III from the Agiad dynasty, who was a minor, and Lycurgus1, of obscure background. Cleomenes’ reforms were reversed, but the Spartans preserved their independance.

In the world around Sparta though, tensions were building up. Rome had recently captured Southern Illyria and Corcyra, reaching the borders of Macedon. The 2nd Punic War between Rome and Carthage was about to erupt, as well as the 4th Syrian War between the Seleucids and the Ptolemies. Meanwhile, the Aetolians, hostile to Macedon and their new ally in Achaea, were leaning towards Ptolemaic Egypt and Rome. The Aetolian League also had allies in the Peloponnese: Elis, Messenia and soon Sparta as well.

In 220 BC the Greek Social War broke out. The Aetolians dispatched raiding parties to the Achaean-Messenian border, trying to keep their wavering Messenian allies in check, while pillaging the Achaean countryside. Aratus protested and called the Achaeans to arms, but he was defeated at the Battle of Caphyae in Arcadia. Philip V - the new king of Macedon - was at first reluctant to intervene, but when the Aetolians allied with the Illyrian Kingdom, a Roman client state, he summoned his league members to Corinth and declared war on Aetolia.

The war soon spread to Crete, while a large Illyrian pirate fleet descended upon Greece. One of the two Illyrian commanders, future king Scerdilaidas, assisted the Aetolian raids in the Peloponnese. The other, Illyrian regent Demetrios of Pharos, pillaged the Aegean Islands before switching sides to Macedon.

In 219 BC the Aetolians tried to recruit Sparta into their war effort. While the Ephors sent them away without agreement, some young men hoping to restore Cleomenes had the Ephors and others killed. But soon the news of Cleomenes’ death in Egypt reached Sparta, and probably at this point the new Ephors appointed Lycurgus and young Agesipolis III as kings. Aetolian envoys returned and the Spartans agreed to an alliance this time. Sparta and Aetolia had already been natural allies during the Cleomenian war; while no direct cooperation is mentioned, the Aetolians had threatened Antigonus III with war if he dared march through their lands on his way to attack the Spartans.

Aetolia, Elis and Sparta attacked the Achaeans from all sides, bringing them close to collapse. Lycurgus managed to capture several small towns and forts. Additionally, the Aetolians raided the sanctuaries of Dion in Macedon and Dodona in Epirus. Roman legions were sent to Illyria once more, forcing Demetrios of Pharos to flee to the Macedonian court. Philip V attacked Aetolia with mixed success, before leaving upon false reports of yet another Dardanian invasion in Macedon. Lycurgus, after recapturing a few border regions, was forced to flee from Sparta, as a man named Chilon and his supporters murdered the Ephors and attempted to revive the Cleomenian constitution. The coup failed within the same year and Lycurgus returned to power.

In 218 BC the 2nd Punic War broke out in the west. In the Peloponnese, Lycurgus launched a failed attack on Messenia who had switched sides. He then occupied Tegea but failed to take the citadel. Philip V took many Peloponnesian cities and granted them to the Achaeans, before attacking Aetolian held Cephalonia. He then turned once more to Aetolia, sacking the sanctuary and league capital of Thermon. Moving against the Spartans he overrun Laconia, while the Ephors moved to depose Lycurgus, who - accused of planning a revolution - fled to Aetolia.

In 217 BC the Achaeans managed to defeat that year’s Aetolian raiders and launched a successful counterattack against Elis. Philip captured the last Aetolian holdings in Thessaly, while the new Ephors considered the charges against Lycurgus to be false and recalled him. Lycurgus once again attacked Messenia without success. The same year, the Peace of Naupactus was agreed upon, with both sides keeping whatever they currently held, a clear but not complete victory for the Macedonian alliance. The Spartans had no major gains or losses, and - possibly at this point -Lycurgus deposed the underage Agesipolis III, becoming the first king of Sparta without a co-ruler. Meanwhile, Hannibal Barca was winning great victories in Italy. In the eastern front, Antiochus’ III ascend to “Greatness” was put to a halt at the major Battle of Raphia by Ptolemy IV, the same decadent Pharaoh who caused Cleomenes’ demise a couple of years earlier.

The last years of Lycurgus reign appear uneventful in Sparta, but we shall keep providing historical context on what is to come next.

Philip V and Hannibal desired cooperation against Rome, but the Roman fleet dominating the Western Mediterranean was a great obstacle. In 216 BC Philip set sail to attack the Roman protectorates in Illyria with a fleet of newly built light galleys. A squadron of quinqueremes though was mistaken for the whole Roman fleet, and the Macedonians sailed back home. In 214 a new attempted was made. This time Philip reached Illyria and besieged Apollonia, but Roman reinforcements caught the Macedonians off guard, causing a panicked retreat and great losses, including the ships. In 213 BC Cleomenes’ arch-nemesis Aratus of Sicyon died, allegedly poisoned by Philip, who soon returned to Illyria by land and for the next two years made considerable gains, including the stronghold of Dimale and the important harbor of Lissus.

After earlier failures, in 211 BC Roman envoys managed to convince the Aetolian League to fight Macedon once again. The Romans were to conduct naval operations and keep any slaves and loot gained, while the Aetolians would focus on land and keep any territorial gains. The Roman fleet began operations in the Ionian Sea to some success. Philip responded by terrorizing or subjugating several pro-Roman and other warlike tribes across his northern frontier, also by improving border fortifications.

In 210 BC Sparta, Elis, Messenia and king Attalus I of Pergamon officially joined the Roman alliance. The Roman-Pergamene fleet dominated the seas and conducted raids for slaves and plunder. The rest of the allies kept Philip busy on land. Around this time Lycurgus of Sparta disappears from history, in the same obscure manner as he had entered it.

The Dictatorship of Machanidas and the Ancient World War (c. 210-207 BC)

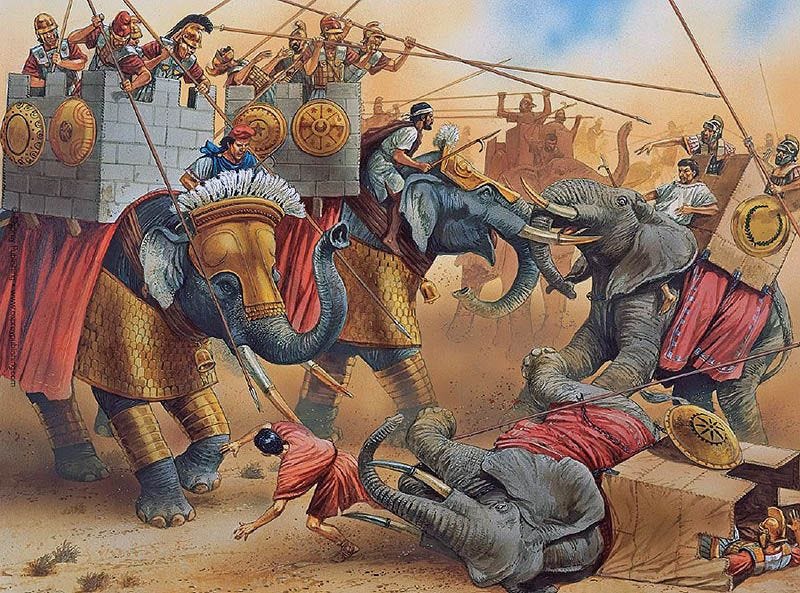

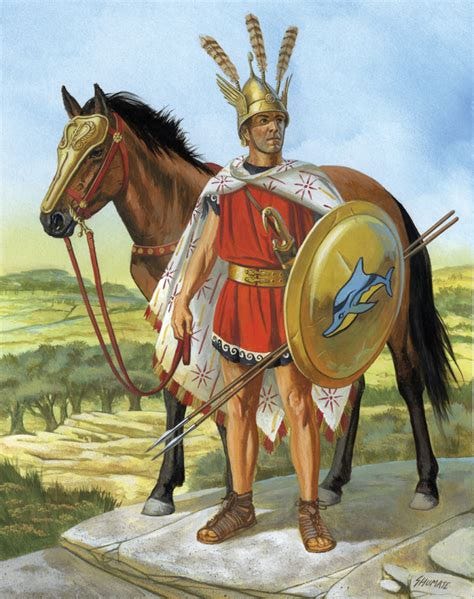

Lycurgus was succeeded by his infant son, Pelops. Machanidas, possibly a former mercenary in service of Sparta, rose to power as his guardian2. It’s tempting to assume that Lycurgus opposed entering the war (or preferred the other side) and was removed by (pro-)Roman intrigue. Machanidas imposed a military dictatorship, respecting neither reformist nor oligarchic laws and desires. He went about with a large army, captured Tegea and campaigned near Argos, too strong of a rival for the Achaeans to face in battle.3

In 209 BC Philip marched south to aid his allies. His passage was blocked near Lamia by Pyrrhias, general of the Aetolians, supported by Roman and Pergamene troops. The Macedonians won two battles inflicting heavy loses and gaining access to the Peloponnese. A Roman attack near Corinth was repelled by Philip’s cavalry and Macedonian forces aided the Achaeans against Machanidas. Philip made gains in Elis, before rushing north to face more Illyrian and Dardanian invasions.4

In 208 BC more Roman-Pergamene naval raids were conducted against Macedonian holdings and allies, failing to take Lemnos but looting Peparethos. While pundering cities in Euboea, Attalus and Publius Sulpicius Galba were caught of guard by Philip, merely escaping by sea. Attalus soon returned to his kingdom, being attacked by Prusias I of Bithynia, a relative of Philip by marriage.

In 207 BC Philip captured many Aetolian cities and sacked the capital of Thermon for the second time. Machanidas campaigned near Elis during the preparations for the Olympic games, but withdrew on the arrival of Philip. Philopoemen, general of the Achaean League, finally dared to face Machanidas in a pitched battle after performing military drills for many months. The Achaeans were victorious near Mantineia; Machanidas was killed in personal combat by Philopoemen, who had also slain Damophantus - cavalry commander of Elis - in a duel earlier in the war.

Rhodes, Egypt and other mercantile states were hurt by major trade disruption; they had been pushing for peace over the last couple of years to no avail. Things started to change when the exhausted Aetolians made a separate peace with Macedon in 206 BC. After a few more confrontations in Illyria, Macedon and Rome finally came to terms the following year. The Macedonians won the war, making gains in Greece and Illyria. The Romans achieved their main objective, as Philip failed to support Hannibal in Italy. Large parts of Greece and Illyria were devastated during the 1st Roman-Macedonian war, during which Rome is often presented as a justified defender.5

The death of Machanidas at Mantineia found the Spartans in unreast yet again. A new king, the strongest since at least Cleomenes III, and in some ways one of the most radical and controversial rulers in history, was about to rise in Sparta.

To be continued… (Part IV)

Some theorize that Lyrcurgus was an Eurypontid king, but there is no real evidence on that. Interestingly, he’s the first Spartan king named after the legendary lawgiver of Sparta. His son, Pelops, uniquely bears the name of the mythic forefather of the Peloponnesians. Polybius claims that Lyrcurgus was a non-royal who got the throne by bribing the Ephors.

It has been claimed that Machanidas was in a band of Tarentine mercenaries employed by Sparta, perhaps even their leader. Tarentine cavalry originated in Tarentum, but the term soon started to be used for any horsemen who fought using similar equipment and tactics.

Our pro-Roman ancient sources aren’t really interested in Roman and allied shady deals around this period, while reports on such deeds by Rome’s rivals and neutral states are pretty common. I’ve seen even highly praised academic work theorize the way I do here, but only on politically convenient cases.

Guesswork on the rise of Darius “the Great” is a prime example of acceptable conspiracy theories; he’s allowed to be the typical scheming easterner. The Empire never does that. At least not its noble forefathers. And of course not its modern incarnation, nor your favorite political party or billionaire. The great conqueror and frequent brutalizer of civilians - and even his own friends - AlexDaGreat? He’s certainly above that.

Besides Machanidas shady rise to power, whether the Achaeans were really weak at this point or Machanidas had significant foreign backing is an interesting question. Lycurgus, in contrast, can’t even deal effectively with Messenia, the weakest Peloponnesian state at the time.

The Spartan army can’t be strong - without major external support - in the 222-207 BC period: Cleomenes lost the war and the vast majority of male adult citizens died at Sellasia in 222 BC. With the reforms reversed, the land is back at the hands of a tiny minority who anyway isn’t that interested in “dieing for Sparta”. The only possibilities for a militarily strong Sparta in those times that I can see are:

Much more than the 5000 or so mercenaries Cleomenes had. Which would require major external aid for a defeated and diminished Sparta.

The Perioikoi somehow becoming fighting machines, and that with the faction promising improved rights for them gone.

Machanidas is an unrecognized military genius.

I think only the first option is really likely, and seeing the geopolitical situation, I propose that Machanidas is a Roman alliance plant that hires troops with Roman and/or Pergamene coin. He even has field artillery at the battle of Mantinea, a pretty rare (and rather expensive) occurrence in Hellenistic battlefields.

I’ll also recognize another possibility: The supposed power of Machanidas is overstated, to increase the glory of Achaean hero Philopoemen in defeating him. After all Machanidas didn’t achieve that much, unless most of his exploits have been lost due to time or enemy scribes.

For much of his wars against Rome, Philip V was frantically running up and down the Balkans, facing threats to Macedon and its allies coming from all sides. A signal fire system was established to give the Macedonians advance warning.

The usual narratives describing this period leave the impression that Philip V of Macedon is an unprovoked aggressor trying to exploit Roman weakness as Hannibal is ravaging Italy. However, it is the Romans who first meddle in Illyria reaching Macedon’s border, and their new Illyrian client state is soon raiding Greece and Macedon. Going a few years back, Philip’s predecessors had ties with the previous pirate state of Agron and Teuta, who had enraged the Romans. Later, Scerdilaidas assisting the pro-Roman Aetolians and Demetrius of Pharos aiding Macedon during the very same expedition (as well as during the Sellasia campaign) further show the complexity of the Illyrian affairs. Both Rome and Macedon were trying to control or direct the situation in Illyria to their own advantage, while Rome was the one to take the first bold step towards direct confrontation.

Perhaps even more annoyingly, Rome, together with - highly praised “hyper civilized” - Attalid Pergamon greatly devastated and slave-raided the Greek shores and largely get away with it even in modern historiography. Maybe I should someday write about Republican Romans and Illustrious Attalids being… pirates?